I recently wrote an op-ed piece for the Guardian in which I suggested that there is too much of an emphasis on ‘infotainment’ in contemporary science journalism and there is too little critical science journalism. The response to the article was unexpectedly strong, provoking some hostile comments on Twitter, and some of the most angry comments seem to indicate a misunderstanding of the core message.

One of the themes that emerged in response to the article was the Us-vs.-Them perception that “scientists” were attacking “journalists”. This was surprising because as a science blogger, I assumed that I, too, was a science journalist. My definitions of scientist and journalist tend to be rather broad and inclusive. I think of scientists with a special interest and expertise in communicating science to a broad readership as science journalists. I also consider journalists with a significant interest and expertise in science as scientists. My inclusive definitions of scientists and journalists have been in part influenced by an article written by Bora Zivkovic, an outstanding science journalist and scientist and the person who inspired me to become a science blogger. As Bora Zivokovic reminds us, scientists and journalists have a lot in common: They are supposed to be critical and skeptical, they obtain and analyze data and they communicate their findings to an audience after carefully evaluating their data. However, it is apparent that some scientists and journalists are protective of their respective domains. Some scientists may not accept science journalists as fellow scientists unless they are part of an active science laboratory. Conversely, some journalists may not accept scientists as fellow journalists unless their primary employer is a media organization. For the purpose of this discussion, I will try to therefore use the more generic term “science writing” instead of “science journalism”.

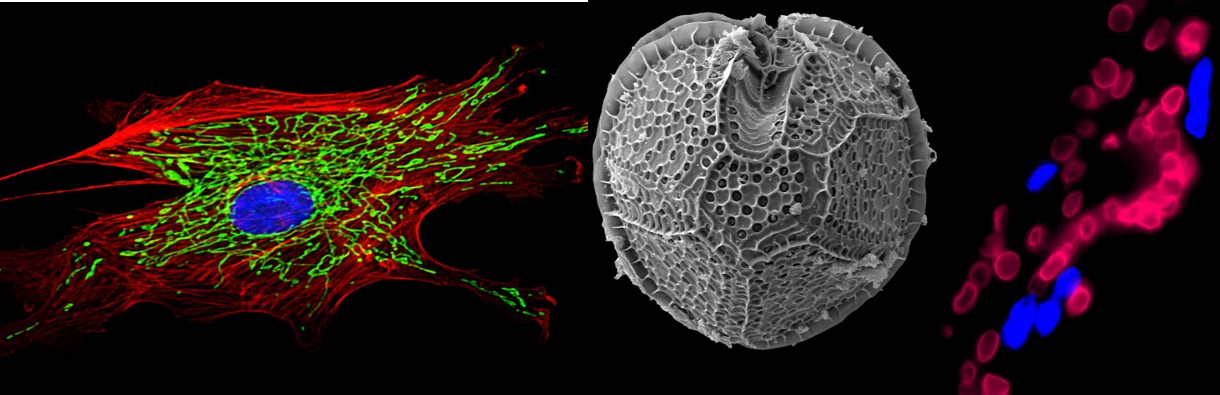

Are infotainment science writing and critical science writing opposites? This was one of the major questions that arose in the Twitter discussion. The schematic below illustrates infotainment and critical science writing.

Although this schematic of a triangle might seem oversimplified, it is a tool that I use to help me in my own science writing. “Critical science writing” (base of the triangle) tends to provide information and critical analysis of scientific research to the readers. Infotainment science writing minimizes the critical analysis of the research and instead focuses on presenting content about scientific research in an entertaining style. Scientific satire as a combination of entertainment and critical analysis was not discussed in the Guardian article, but I think that this too is a form of science writing that should be encouraged.

Articles or blog-posts can fall anywhere within this triangle, which is why infotainment and critical science writing are not true dichotomies, they just have distinct emphases. Infotainment science writing can include some degree of critical analysis, and critical science writing can be somewhat entertaining. However, it is rare for science writing (or other forms of writing) to strike a balance that is able to include accurate scientific information, entertainment, as well as a profound critical analysis that challenges the scientific methodology or scientific establishment, all in one article. In American political journalism, Jon Stewart and the Daily Show are perhaps one example of how one can inform, entertain and be critical – all in one succinct package. Currently, contemporary science writing which is informative and entertaining (‘infotainment’), rarely challenges the scientific establishment the way Jon Stewart challenges the political establishment.

Is ‘infotainment’ a derogatory term? Some readers of the Guardian article assumed that I was not only claiming that all science journalism is ‘infotainment’, but also putting down ‘infotainment’ science journalism. There is nothing wrong with writing about science in an informative and entertaining manner, therefore ‘infotainment’ science writing should not be construed as a derogatory term. There are differences between good and sloppy infotainment science writing. Good infotainment science writing is accurate in terms of the scientific information it conveys, whereas sloppy infotainment science writing discards scientific accuracy to maximize hype and entertainment value. Similarly, there is good and sloppy critical science writing. Good critical science writing is painstakingly careful in the analysis of the scientific data and its scientific context by reviewing numerous other related scientific studies in the field and putting the scientific work in perspective. Sloppy critical science writing, on the other hand, might just single out one scientific study and attempt to discredit a whole area of research without examining context. Examples of sloppy critical science writing can be found in the anti-global warming literature, which hones in on a few minor scientific discrepancies, but ignores the fact that 98-99% of climate scientists agree on the fact that humans are the primary cause of global warming.

Instead of just discussing these distinctions in abstract terms, I will use some of my prior blog-posts to illustrate differences between different types of science writing, such as infotainment, critical science writing or scientific satire. I find it easier to critique my own science writing than that of other science writers, probably because I am plagued by the same self-doubts that most writers struggle with. The following analysis may be helpful for other science writers who want to see where their articles and blog-posts fall on the information – critical analysis – entertainment spectrum.

A. Infotainment science writing

Infotainment science writing allows me to write about exciting or unusual new discoveries in a fairly manageable amount of time, without having to extensively review the literature in the field or perform an in-depth analysis of the statistics and every figure in the study under discussion. After providing some background for the non-specialist reader, one can focus on faithfully reporting the data in the paper and the implications of the work without discussing all the major caveats and pitfalls in the published paper. This writing provides a bit of an escapist pleasure for me, because so much of my time as a scientist is spent performing a critical analysis of the experimental data acquired in my own laboratory or in-depth reviews of scientific manuscripts and grants of either collaborators or as a peer reviewer. Infotainment science writing is a reminder of the big picture, excitement and promise of science, even though it might gloss over certain important experimental flaws and caveats of scientific studies.

Infotainment Science Writing Example 1: Using Viagra To Burn Fat

This blog-post discusses a paper published in the FASEB Journal, which suggested that white (“bad”) fat cells could be converted into brown (“good”) fat cells using Viagra. The study reminded me of a collision between two groups of spam emails: weight loss meets Viagra. The blog-post provides background on white and brown adipose tissue and then describes the key findings of the paper. A few limitations of the study are mentioned, such as the fact that the researchers never document weight loss in the mice they treated, as well as the fact that the paper ignores long-term consequences of chronic Viagra treatment. The reason I consider this piece an infotainment style of science writing is that there were numerous criticisms of the research study that could have been brought to the attention of the readers. The researchers concluded the fat cells were being converted into brown fat using only indirect measures without adequately measuring the metabolic activity and energy expenditure. It is not clear why the researchers did not extend the duration of the animal studies to show that the Viagra treatment could induce weight loss. If all of these criticisms had been included in the blog-post, the fun Viagra-weight loss idea would have been drowned in a whirlpool of details.

Infotainment Science Writing Example 2: The Healing Power of Sweat Glands

The idea of “icky” sweat glands promoting wound healing was the main hook. Smelly apocrine sweat glands versus eccrine sweat glands are defined in the background of this blog-post, and the findings of the paper published in the American Journal of Pathology are summarized. Limitations of the study included little investigation of the mechanism of regeneration, whether cells primarily proliferate or differentiate to promote the wound healing and an important question: Does sweating itself affect the regenerative capacity of the sweat glands? Although these limitations are briefly mentioned in the blog-post, they are not discussed in-depth and there is no comparison made between the observed wound healing effects of sweat gland cells to the wound healing capacity of other cells. This blog-post is heavy on the “information” end, and it provides little entertainment, other than evoking the image of a healing sweat gland.

B. Critical science writing

Critical science writing is exceedingly difficult because it is time-consuming and challenging to present critiques of scientific studies in a jargon-free manner. An infotainment science blog-post can be written in a matter of a few hours. A critical science writing piece, on the other hand, requires an in-depth review of multiple studies in the field to better understand the limitations and strengths of each report.

Critical Science Writing Example 1: Bone Marrow Cell Infusions Do NOT Improve Cardiac Function After Heart Attack

This blog-post describes an important negative study conducted in Switzerland. Bone marrow cells were injected into the hearts of patients in one of the largest randomized cardiovascular cell therapy trials performed to date. The researchers found no benefit of the cell injections on cardiac function. This research has important implications because it could stave off quack medicine. Clinics in some countries offer “miracle cures” to cardiovascular patients, claiming that the stem cells in the bone marrow will heal their diseased hearts. Desperate patients, who fall for these scams, fly to other countries, undergo risky procedures and end up spending $20,000 or $40,000 out of pocket for treatments that simply do not work. This blog-post is in the critical science writing category because it not only mentions some limitations of the Swiss study, but also puts the clinical trial into context of the problems associated with unproven therapies. It does not specifically discuss other bone marrow injection studies, but it provides a link to an editorial I wrote for an academic journal which contains all the pertinent references. A number of readers of the Guardian article raised the question whether one can make such critical science writing appear entertaining, but I am not sure how to incorporate entertainment into this type of an analysis.

Critical Science Writing Example 2: Cellular Alchemy: Converting Fibroblasts Into Heart Cells

This blog-post was a review of multiple distinct studies on converting fibroblasts – either found in the skin or the hearts – into beating heart cells. The various research groups described the outcomes of their research, but the studies were not perfect replications of each other. For example, one study that reported a very low efficiency of fibroblast conversion not only used cells derived from older animals but also used a different virus to introduce the genes. The challenge for a critical science writer is to decide which of these differences need to be highlighted, because obviously not all differences and discrepancies can be adequately accommodated in a single article or blog-post. I decided to highlight the electrical heterogeneity of the generated cells as the major limitation of the research because this seemed like the most likely problem when trying to move this work forward into clinical therapies. Regenerating a damaged heart following a heart attack would be the ultimate goal, but do we really want to create islands of heart cells that have distinct electrical properties and could give rise to heart rhythm problems?

C. Science Satire

In closing, I just want to briefly mention scientific satire – satirical or humorous descriptions of real-life science. One of the best science satire websites is PhD Comics, because the comics do a brilliant job of portraying real world science issues, such as the misery of PhD students and the vicious cycle of not having enough research funding to apply for research funding. My own attempts at scientific satire take the form of spoof news articles such as “Professor Hands Out “Erase Undesirable Data Points” Coupons To PhD Students” or “Academic Publisher Unveils New Journal Which Prevents All Access To Its Content”. Science satire is usually not informative, but it can provide entertainment and some critical introspection. This kind of satire is best suited for people with experiences that allow them to understand inside jokes. I hope that we will see more writing that satirizes the working world of how scientists interpret data, compete for tenure and grants or interact with graduate students.

//storify.com/jalees_rehman/reactions-to-critical-science-journalism-piece-in.js[View the story “Reactions to the “Critical Science Journalism” piece in The Guardian” on Storify]

Pingback: [BLOCKED BY STBV] Jornalismo de ciência com olhar crítico, precisa-se : Ponto Media

There’s so much wrong here that I don’t have time to fisk it all, so I’ll home in on a couple of points here.

First, science journalists are not scientists, and scientists are not science journalists; just as political journalists are not politicians, and politicians are not political journalists. This is not least because one of the primary functions of a science journalist should be to hold scientists and scientific institutions to account, as we see in the case of e.g. RetractionWatch. Too many journalists forget that, and the result is Susan Greenfield using her influence with newspapers to push unevidenced theories on the public, or the churnalism of press releases that you rightly criticize. The interests of scientists and science journalists may sometimes – even often – be aligned, but that does not mean we are on the same side or that we have the same aims.

Second, there are very good criticisms out there already of the (I would argue poor) state of science reporting. You don’t seem to have read or understood any of them, and seem hell-bent on trying to impose this ill-thought-out ontology you’ve come up with. It’s like watching somebody blunder into immunology for the first time and declare they’ve thought up a new model that negates Matzinger’s danger theory based on some stuff they read on Wikipedia. The ‘triangle’ above is a new nadir in this effort. Your categories in general make no sense. Again, critical science writing is not in opposition to entertainment, and satire is not in opposition to information. The situation isn’t helped by your insistence on using fraught terms like ‘infotainment’, which have very different definitions in different places.

If you want to understand the problems in science journalism, you need to understand the industry. Much output is from non-specialist journalists operating under brutal time constraints and borrowing heavily from easily available sources, typically press releases (some of the worst of which are from scientific institutions). Only a couple of newspapers in the UK have substantial science sections now. There tend to be very cosy relationships in the UK between science journalists and science institutions, arguably too cosy at times. I could go on, but hopefully you get the point.

Shit journalism is shit journalism, whether it’s satire, entertainment, long-form, short-form, whatever – the same standards generally should apply. That they don’t has a lot more to do with the nature of the changing industry than with people’s desire to entertain.

LikeLike

Dear Martin,

1. Scientists versus Journalists:

Scientists and journalists have very different roles, as you correctly point out. Journalists are supposed to challenge the establishment, political journalists challenge the political establishment and science journalists are supposed to challenge the scientific establishment. You correctly point out that journalism suffers when the relationships between journalists and the establishment became too “cozy” – this is true for political journalism and for science journalism.

However, we live in a world in which many of us have multiple identities and we have to learn how to deal with conflicts that may arise between these identities. Political journalists often vote, donate money to specific campaigns and many of them are members of political parties, have worked for political campaigns and even run for political office or held a political office in the past. Nevertheless, they have to ensure that their personal political biases do not cloud their judgement and professional integrity as journalists.

The same goes for science journalists. Many good science journalists or science writers have worked in science labs, some of them still actively work in a science lab. The blogging platform has given rise to science writers / science journalists who are able to hold multiple jobs and thus multiple identities. Some science journalists or writers no longer work in an active science laboratory, but did so for many years prior to becoming full-time writers. Do they stop being “scientists” just because they no longer hold a pipette or culture cells?

It is important that they realize there might be potential conflicts between their roles as science writers / science journalists on the one hand and being part (or having been part) of the scientific establishment on the other hand.

Instead of the old-fashioned way of framing this debate as a “scientists versus journalists” debate, I think it is better to state that there are different types of science journalism.

Bora Zivkovic used the expressions “typology of journalism” and “multitudes of journalisms” to describe this:

http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/a-blog-around-the-clock/2012/01/17/scio12-multitudes-of-sciences-multitudes-of-journalisms-and-the-disappearance-of-the-quote/

Not every form of political journalism is critical and investigative. Many political news articles merely report about new political development without performing an in-depth critique, analysis or investigation. Not every political journalist in the US will uncover a Watergate scandal, even thought they may aspire to do so.

The same is true for science journalism. I think every science journalist can go through his or her own articles and identify how much critical analysis and independent investigation of the presented research each one contains.

I agree with Bora and I think that by re-framing the debate as one about types of journalisms (varying emphases on providing accurate scientific information, on entertaining readers and on performing an independent critical analysis of the research) we can overcome the alleged scientists vs journalists impasse.

2. The industry:

Your comments on the journalism industry are spot on, and I think they apply to political journalism as well. Magazines that have provided critical and investigative political journalism are often struggling and do not have the resources. As you point out, the same is true for science journalism. For an in-depth critical investigation of a new research study, a science journalist would need the time to review and read multiple original research papers, carefully review the data and go over it to check for errors and discrepancies in the experimental design or analysis (the “science” equivalent of political fact-checking), interview the researchers, investigate financial biases and incentives of the researchers, seek out and interview dissenting scientists, etc.

This would require time and resources that are not available to most science journalists. I think that many science journalists would want to engage in such a form of investigative and critical science journalism but the constraints of their work make it nearly impossible. However, if we publicly discuss the importance of critical science journalism (and how it is different from just reporting on scientific discoveries), it might be be possible to convince media organizations to either invest in more in this form of science journalism and provide the resources to their journalists or help science journalists crowd-fund their investigate science journalism.

3. “Shit journalism is shit journalism”

This oversimplification ignores the fact that not every type of journalism has the same goal. A journalist who reports about a disaster does not necessarily need to provide an in-depth analysis of why the disaster occurred and what steps could have been taken to limit the damage. “Shit journalism” in the context of primarily reporting about a disaster would for example consist of communicating wrong facts and exaggerating the damage. On the other hand, an investigative journalism article about the causes of the disaster would be “shit journalism”, if it performed an inadequate analysis and suppressed information that was uncovered during the investigation.

LikeLike

Pingback: [BLOCKED BY STBV] #SciLogs Weekly Roundup: Charles Darwin, Biocalculator, Infotainment, Woman Scientist, National Champion For Science | Community Blog

Pingback: [BLOCKED BY STBV] NRCD 25 May 13: True Confessions Edition | New Religion and Culture Daily